If you’ve moved to Vim from an editor like Notepad++ or TextMate, you’ll be used to working with the idea of tabs in a text editor in a certain way. Specifically, a tab represents an open file; while the tab’s there, you’ve got an open file, as soon as you close it, it goes away. This one-to-one correspondence is pretty straightforward and is analogous to using tabs in a web browser; while the page is open, there’s a tab there, and you have one page per tab, and one tab per page.

Vim has a system for tabs as well, but it works in a completely different way from how text editors and browsers do. Beginners with Vim are often frustrated by this because the model for tabs is used so consistently in pretty much every other program they’re accustomed to, and they might end up spending a lot of fruitless time trying to force Vim to follow the same model through its configuration.

I think a good way to understand the differences in concept and usage between Vim’s three levels of view abstraction — buffers, windows, and tabs — is to learn how to use each from the ground up. So let’s start with buffers.

Buffers

A buffer in Vim is probably best thought of for most users as an open instance of a file, that may not necessarily be visible on the current screen. There’s probably a more accurate technical definition as a buffer need not actually correspond to a file on your disk, but it’ll work for our purposes.

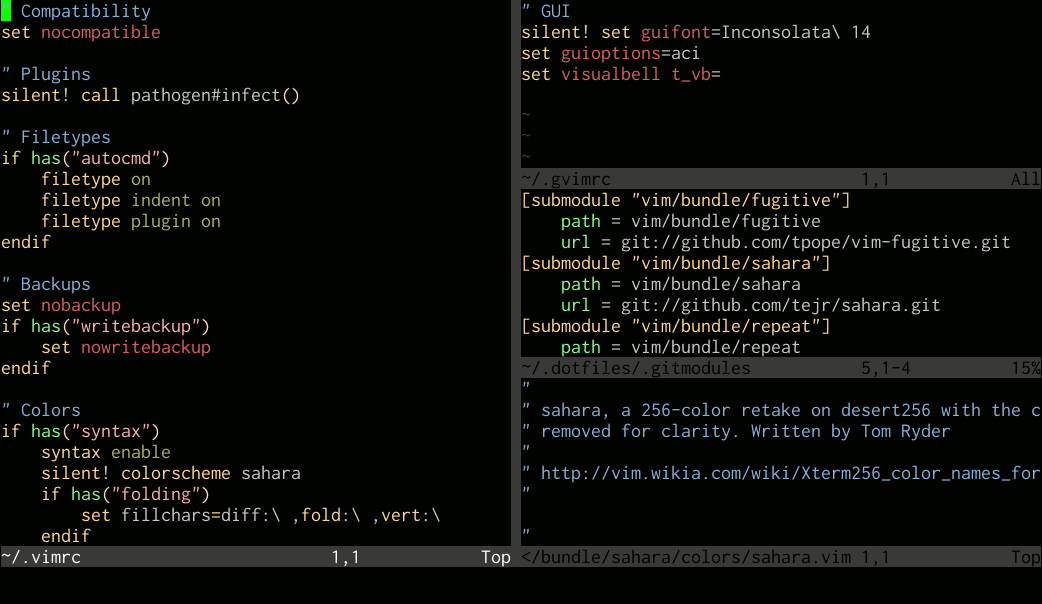

When you open a single file in Vim, that file gets put into a buffer, and it’s

the only buffer there on startup. If this buffer is unmodified (or if you’re

using hidden), and you open another file with :edit, that buffer goes into

the background and you start working with the new file. The previous buffer

only goes away when you explicitly delete it with a call to :quit or

:bdelete, and even then it’s still recoverable unless you do :bwipe.

By default, a buffer can only be in the background like this if it’s

unmodified. You can remove this restriction if you like with the :set hidden

option.

You can get a quick list of the buffers open in a Vim session with :ls. This

all means that when most people think of tabs in more familiar text editors,

the idea of a buffer in Vim is actually closest to what they’re thinking.

Windows

A window in Vim is a viewport onto a single buffer. When you open a new

window with :split or :vsplit, you can include a filename in the call. This

opens the file in a new buffer, and then opens a new window as a view onto it.

A buffer can be viewed in multiple windows within a single Vim session; you

could have a hundred windows editing the same buffer if you wanted to.

Tabs

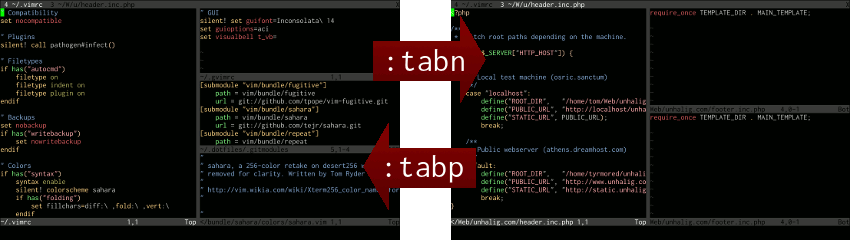

Finally, a tab in Vim is a collection of one or more windows. The best

way to think of tabs, therefore, is as enabling you to group windows usefully.

For example, if you were working on code for both a client program and a server

program, you could have the files for the client program open in the first tab,

perhaps in three or four windows, and the files for the server program open in

another, which could be, say, seven windows. You can then flick back and forth

between the tabs using :tabn and :tabp.

This model of buffers, windows, and tabs is quite a bit more intricate than in other editors, and the terms are sometimes confusing. However, if you know a bit about how they’re supposed to work, you get a great deal more control over the layout of your editing sessions as a result. Personally, I find I rarely need tabs as with a monitor of sufficient size it suffices to keep two or three windows open at a time when working on sets of files, but on the odd occasion I do need tabs, I do find them tremendously useful.

Thanks to Hacker News users anonymous and m0shen for pointing out potential confusion with the :set hidden option and the :bdelete command.