PuTTY is a terminal emulator with a free software license, including an SSH client. While it has cross-platform ports, it’s used most frequently on Windows systems, because they otherwise lack a built-in terminal emulator that interoperates well with Unix-style TTY systems.

While it’s very popular and useful, PuTTY’s defaults are quite old, and are chosen for compatibility reasons rather than to take advantage of all the features of a more complete terminal emulator. For new users, this is likely an advantage as it can avoid confusion, but more advanced users who need to use a Windows client to connect to a modern GNU/Linux system may find the defaults frustrating, particularly when connecting to a more capable and custom-configured server.

Here are a few of the problems with the default configuration:

- It identifies itself as an

xterm(1), whenterminfo(5)definitions are available namedputtyandputty-256color, which more precisely define what the terminal can and cannot do, and their various custom escape sequences. - It only allows 16 colors, where most modern terminals are capable of using 256; this is partly tied into the terminal type definition.

- It doesn’t use UTF-8 by default, which should be used whenever

possible for reasons of interoperability and compatibility, and is

well-supported by modern

localedefinitions on GNU/Linux. - It uses Courier New, a workable but rather harsh monospace font, which should be swapped out for something more modern if available.

- It uses audible terminal bells, which tend to be annoying.

- Its default palette based on

xterm(1)is rather garish and harsh; softer colors are more pleasant to read.

All of these things are fixable.

Terminal type

Usually the most important thing in getting a terminal working smoothly is to

make sure it identifies itself correctly to the machine to which it’s

connecting, using an appropriate $TERM string. By default, PuTTY identifies

itself as an xterm(1) terminal emulator, which most systems will support.

However, there’s a terminfo(5) definition for putty and putty-256color

available as part of ncurses, and if you have it available on your system

then you should use it, as it slightly more precisely describes the features

available to PuTTY as a terminal emulator.

You can check that you have the appropriate terminfo(5) definition installed

by looking in /usr/share/terminfo/p:

$ ls -1 /usr/share/terminfo/p/putty*

/usr/share/terminfo/p/putty

/usr/share/terminfo/p/putty-256color

/usr/share/terminfo/p/putty-sco

/usr/share/terminfo/p/putty-vt100

On Debian and Ubuntu systems, these files can be installed with:

# apt-get install ncurses-term

If you can’t install the files via your system’s package manager, you can also

keep a private repository of terminfo(5) files in your home directory, in

a directory called .terminfo:

$ ls -1 $HOME/.terminfo/p

putty

putty-256color

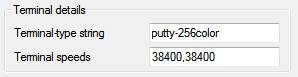

Once you have this definition installed, you can instruct PuTTY to identify

with that $TERM string in the Connection > Data section:

Here, I’ve used putty-256color; if you don’t need or want a 256 color

terminal you could just use putty.

Once connected, make sure that your $TERM string matches what you specified,

and hasn’t been mangled by any of your shell or terminal configurations:

$ echo $TERM

putty-256color

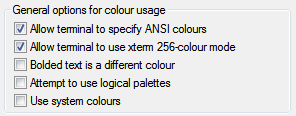

Color space

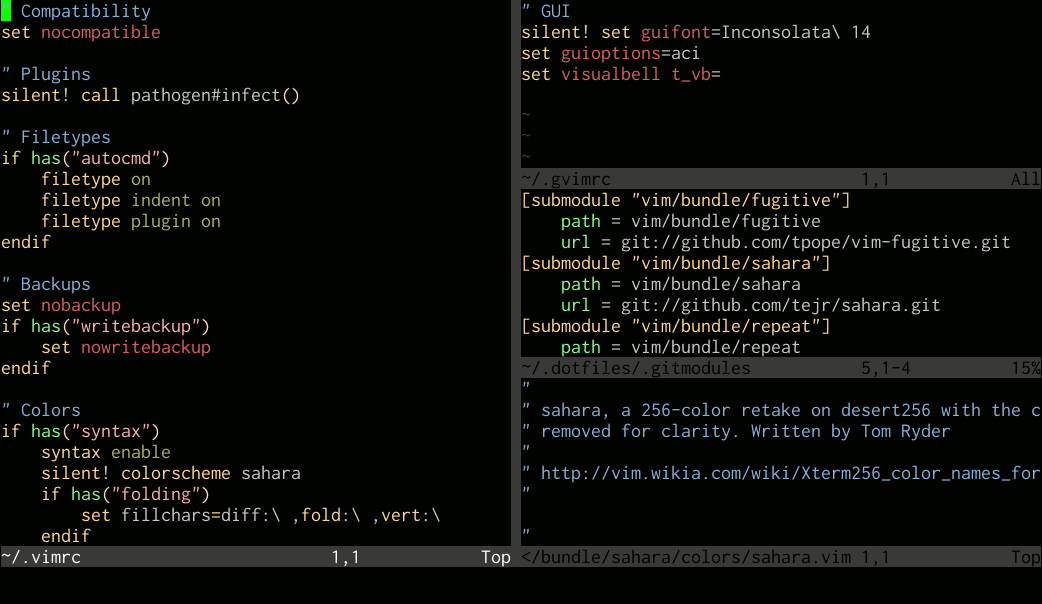

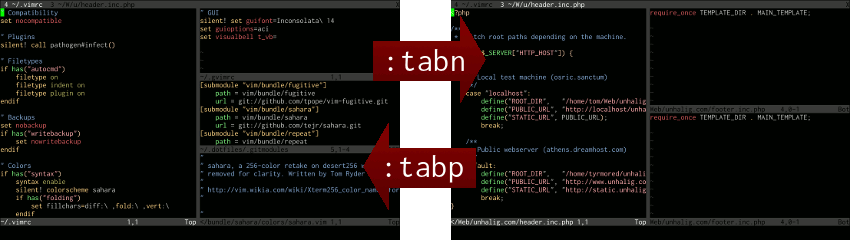

Certain command line applications like Vim and Tmux can take advantage of

a full 256 colors in the terminal. If you’d like to use this, set

PuTTY’s $TERM string to putty-256color as outlined above, and select

Allow terminal to use xterm 256-colour mode in Window > Colours:

You can test this is working by using a 256 color application, or by trying out

the terminal colours directly in your shell using tput:

$ for ((color = 0; color <= 255; color++)); do

> tput setaf "$color"

> printf "test"

> done

If you see the word test in many different colors, then things are probably

working. Type reset to fix your terminal after this:

$ reset

Using UTF-8

If you’re connecting to a modern GNU/Linux system, it’s likely that you’re

using a UTF-8 locale. You can check which one by typing locale. In my case,

I’m using the en_NZ locale with UTF-8 character encoding:

$ locale

LANG=en_NZ.UTF-8

LANGUAGE=en_NZ:en

LC_CTYPE="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_NUMERIC="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_TIME="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_COLLATE="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_MONETARY="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_MESSAGES="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_PAPER="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_NAME="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_ADDRESS="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_TELEPHONE="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_MEASUREMENT="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_IDENTIFICATION="en_NZ.UTF-8"

LC_ALL=

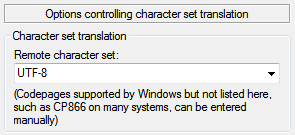

If the output of locale does show you’re using a UTF-8 character encoding,

then you should configure PuTTY to interpret terminal output using that

character set; it can’t detect it automatically (which isn’t PuTTY’s fault;

it’s a known hard problem). You do this in the Window > Translation

section:

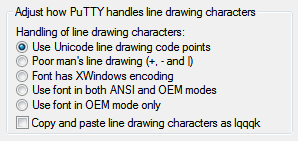

While you’re in this section, it’s best to choose the Use Unicode line drawing code points option as well. Line-drawing characters are most likely to work properly with this setting for UTF-8 locales and modern fonts:

If Unicode and its various encodings is new to you, I highly recommend Joel Spolsky’s classic article about what programmers should know about both.

Fonts

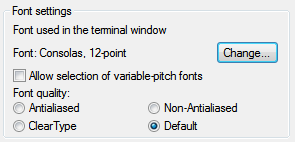

Courier New is a workable monospace font, but modern Windows systems include Consolas, a much nicer terminal font. You can change this in the Window > Appearance section:

There’s no reason you can’t use another favourite Bitmap or TrueType font instead once it’s installed on your system; DejaVu Sans Mono, Inconsolata, and Terminus are popular alternatives. I personally favor Ubuntu Mono.

Bells

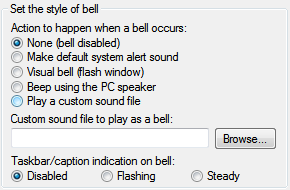

Terminal bells by default in PuTTY emit the system alert sound. Most people find this annoying; some sort of visual bell tends to be much better if you want to use the bell at all. Configure this in Terminal > Bell:

Given the purpose of the alert is to draw attention to the window, I find

that using a flashing taskbar icon works well; I use this to draw my attention

to my prompt being displayed after a long task completes, or if someone

mentions my name or directly messages me in irssi(1).

Another option is using the Visual bell (flash window) option, but I personally find this even worse than the audible bell.

Default palette

The default colours for PuTTY are rather like those used in xterm(1), and

hence rather harsh, particularly if you’re used to the slightly more subdued

colorscheme of terminal emulators like gnome-terminal(1), or have customized

your palette to something like Solarized.

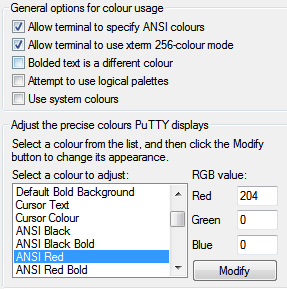

If you have decimal RGB values for the colours you’d prefer to use, you can enter those in the Window > Colours section, making sure that Use system colours and Attempt to use logical palettes are unchecked:

There are a few other default annoyances in PuTTY, but the above are the ones that seem to annoy advanced users most frequently. Dag Wieers has a similar post with a few more defaults to fix.