As users grow more familiar with the feature set available to them on UNIX-like operating systems, and grow more comfortable using the command line, they will find more often that they develop their own routines for solving problems using their preferred tools, often repeatedly solving the same problem in the same way. You can usually tell if you’ve entered this stage if one or more of the below applies:

- You repeatedly search the web for the same long commands to copy-paste.

- You type a particular long command so often it’s gone into muscle memory, and you type it without thinking.

- You have a text file somewhere with a list of useful commands to solve some frequently recurring problem or task, and you copy-paste from it a lot.

- You’re keeping large amounts of history so you can search back through

commands you ran weeks or months ago with

^R, to find the last time an instance of a problem came up, and getting angry when you realize it’s fallen away off the end of your history file. - You’ve found that you prefer to run a tool like

ls(1)more often with a non-default flag than without it;-lis a common example.

You can definitely accomplish a lot of work quickly with shoving the output of some monolithic program through a terse one-liner to get the information you want, or by developing muscle memory for your chosen toolbox and oft-repeated commands, but if you want to apply more discipline and automation to managing these sorts of tasks, it may be useful for you to explore more rigorously defining your own commands for use during your shell sessions, or for automation purposes.

This is consistent with the original idea of the Unix shell as a programming environment; the tools provided by the base system are intentionally very general, not prescribing how they’re used, an approach which allows the user to build and customize their own command set as appropriate for their system’s needs, even on a per-user basis.

What this all means is that you need not treat the tools available to you as holy writ. To leverage the Unix philosophy’s real power, you should consider customizing and extending the command set in ways that are useful to you, refining them as you go, and sharing those extensions and tweaks if they may be useful to others. We’ll discuss here a few methods for implementing custom commands, and where and how to apply them.

Aliases

The first step users take toward customizing the behaviour of their shell tools

is often to define shell aliases in their shell’s startup file, usually

specifically for interactive sessions; for Bash, this is usually ~/.bashrc.

Some aliases are so common that they’re included as commented-out suggestions

in the default ~/.bashrc file for new users. For example, on Debian systems,

the following alias is defined by default if the dircolors(1) tool is

available for coloring ls(1) output by filetype:

alias ls='ls --color=auto'

With this defined at startup, invoking ls, with or without other arguments,

will expand to run ls --color=auto, including any given arguments on the end

as well.

In the same block of that file, but commented out, are suggestions for other

aliases to enable coloured output for GNU versions of the dir and grep

tools:

#alias dir='dir --color=auto'

#alias vdir='vdir --color=auto'

#alias grep='grep --color=auto'

#alias fgrep='fgrep --color=auto'

#alias egrep='egrep --color=auto'

Further down still, there are some suggestions for different methods of

invoking ls:

#alias ll='ls -l'

#alias la='ls -A'

#alias l='ls -CF'

Commenting these out would make ll, la, and l work as commands during an

interactive session, with the appropriate options added to the call.

You can check the aliases defined in your current shell session by

typing alias with no arguments:

$ alias

alias ls='ls --color=auto'

Aliases are convenient ways to add options to commands, and are very common

features of ~/.bashrc files shared on the web. They also work in

POSIX-conforming shells besides Bash. However, for general use, they aren’t

very sophisticated. For one thing, you can’t process arguments with

them:

# An attempt to write an alias that searches for a given pattern in a fixed

# file; doesn't work because aliases don't expand parameters

alias grepvim='grep "$1" ~/.vimrc'

They also don’t work for defining new commands within scripts for certain shells:

#!/bin/bash

alias ll='ls -l'

ll

When saved in a file as test, made executable, and run, this script fails:

./test: line 3: ll: command not found

So, once you understand how aliases work so you can read them when others define them in startup files, my suggestion is there’s no point writing any. Aside from some very niche evaluation tricks, they have no functional advantages over shell functions and scripts.

Functions

A more flexible method for defining custom commands for an interactive shell

(or within a script) is to use a shell function. We could declare our ll

function in a Bash startup file as a function instead of an alias like so:

# Shortcut to call ls(1) with the -l flag

ll() {

command ls -l "$@"

}

Note the use of the command builtin here to specify that the ll function

should invoke the program named ls, and not any function named ls. This

is particularly important when writing a function wrapper around a command, to

stop an infinite loop where the function calls itself indefinitely:

# Always add -q to invocations of gdb(1)

gdb() {

command gdb -q "$@"

}

In both examples, note also the use of the "$@" expansion, to add to the

final command line any arguments given to the function. We wrap it in double

quotes to stop spaces and other shell metacharacters in the arguments causing

problems. This means that the ll command will work correctly if you were to

pass it further options and/or one or more directories as arguments:

$ ll -a

$ ll ~/.config

Shell functions declared in this way are specified by POSIX for Bourne-style

shells, so they should work in your shell of choice, including Bash, dash,

Korn shell, and Zsh. They can also be used within scripts, allowing you to

abstract away multiple instances of similar commands to improve the clarity of

your script, in much the same way the basics of functions work in

general-purpose programming languages.

Functions are a good and portable way to approach adding features to your

interactive shell; written carefully, they even allow you to port features you

might like from other shells into your shell of choice. I’m fond of taking

commands I like from Korn shell or Zsh and implementing them in Bash or POSIX

shell functions, such as Zsh’s vared or its two-argument cd

features.

If you end up writing a lot of shell functions, you should consider putting them into separate configuration subfiles to keep your shell’s primary startup file from becoming unmanageably large.

Examples from the author

You can take a look at some of the shell functions I have defined here that are useful to me in general shell usage; a lot of these amount to implementing convenience features that I wish my shell had, especially for quick directory navigation, or adding options to commands:

Other examples

Variables in shell functions

You can manipulate variables within shell functions, too:

# Print the filename of a path, stripping off its leading path and

# extension

fn() {

name=$1

name=${name##*/}

name=${name%.*}

printf '%s\n' "$name"

}

This works fine, but the catch is that after the function is done, the value

for name will still be defined in the shell, and will overwrite whatever was

in there previously:

$ printf '%s\n' "$name"

foobar

$ fn /home/you/Task_List.doc

Task_List

$ printf '%s\n' "$name"

Task_List

This may be desirable if you actually want the function to change some aspect of your current shell session, such as managing variables or changing the working directory. If you don’t want that, you will probably want to find some means of avoiding name collisions in your variables.

If your function is only for use with a shell that provides the local (Bash)

or typeset (Ksh) features, you can declare the variable as local to the

function to remove its global scope, to prevent this happening:

# Bash-like

fn() {

local name

name=$1

name=${name##*/}

name=${name%.*}

printf '%s\n' "$name"

}

# Ksh-like

# Note different syntax for first line

function fn {

typeset name

name=$1

name=${name##*/}

name=${name%.*}

printf '%s\n' "$name"

}

If you’re using a shell that lacks these features, or you want to aim for POSIX compatibility, things are a little trickier, since local function variables aren’t specified by the standard. One option is to use a subshell, so that the variables are only defined for the duration of the function:

# POSIX; note we're using plain parentheses rather than curly brackets, for

# a subshell

fn() (

name=$1

name=${name##*/}

name=${name%.*}

printf '%s\n' "$name"

)

# POSIX; alternative approach using command substitution:

fn() {

printf '%s\n' "$(

name=$1

name=${name##*/}

name=${name%.*}

printf %s "$name"

)"

}

This subshell method also allows you to change directory with cd within a

function without changing the working directory of the user’s interactive

shell, or to change shell options with set or Bash options with shopt only

temporarily for the purposes of the function.

Another method to deal with variables is to manipulate the positional

parameters directly ($1, $2 … ) with set, since they are local to

the function call too:

# POSIX; using positional parameters

fn() {

set -- "${1##*/}"

set -- "${1%.*}"

printf '%s\n' "$1"

}

These methods work well, and can sometimes even be combined, but they’re

awkward to write, and harder to read than the modern shell versions. If you

only need your functions to work with your modern shell, I recommend just using

local or typeset. The Bash Guide on Greg’s Wiki has a very thorough

breakdown of functions in Bash, if you want to read about this and other

aspects of functions in more detail.

Keeping functions for later

As you get comfortable with defining and using functions during an interactive session, you might define them in ad-hoc ways on the command line for calling in a loop or some other similar circumstance, just to solve a task in that moment.

As an example, I recently made an ad-hoc function called monit to run a set

of commands for its hostname argument that together established different types

of monitoring system checks, using an existing script called nmfs:

$ monit() { nmfs "$1" Ping Y ; nmfs "$1" HTTP Y ; nmfs "$1" SNMP Y ; }

$ for host in webhost{1..10} ; do

> monit "$host"

> done

After that task was done, I realized I was likely to use the monit command

interactively again, so I decided to keep it. Shell functions only last as long

as the current shell, so if you want to make them permanent, you need to store

their definitions somewhere in your startup files. If you’re using Bash, and

you’re content to just add things to the end of your ~/.bashrc file, you

could just do something like this:

$ declare -f monit >> ~/.bashrc

That would append the existing definition of monit in parseable form to your

~/.bashrc file, and the monit function would then be loaded and available

to you for future interactive sessions. Later on, I ended up converting monit

into a shell script, as its use wasn’t limited to just an interactive shell.

If you want a more robust approach to keeping functions like this for Bash permanently, I wrote a tool called Bashkeep, which allows you to quickly store functions and variables defined in your current shell into separate and appropriately-named files, including viewing and managing the list of names conveniently:

$ keep monit

$ keep

monit

$ ls ~/.bashkeep.d

monit.bash

$ keep -d monit

Scripts

Shell functions are a great way to portably customize behaviour you want for

your interactive shell, but if a task isn’t specific only to an interactive

shell context, you should instead consider putting it into its own script

whether written in shell or not, to be invoked somewhere from your PATH. This

makes the script useable in contexts besides an interactive shell with your

personal configuration loaded, for example from within another script, by

another user, or by an X11 session called by something like dmenu.

Even if your set of commands is only a few lines long, if you need to call it often–especially with reference to other scripts and in varying contexts– making it into a generally-available shell script has many advantages.

/usr/local/bin

Users making their own scripts often start by putting them in /usr/local/bin

and making them executable with sudo chmod +x, since many Unix systems

include this directory in the system PATH. If you want a script to be

generally available to all users on a system, this is a reasonable approach.

However, if the script is just something for your own personal use, or if you

don’t have the permissions necessary to write to this system path, it may be

preferable to have your own directory for logical binaries, including scripts.

Private bindir

Unix-like users who do this seem to vary in where they choose to put their private logical binaries directory. I’ve seen each of the below used or recommended:

~/bin~/.bin~/.local/bin~/Scripts

I personally favour ~/.local/bin, but you can put your scripts wherever they

best fit into your HOME directory layout. You may want to choose something

that fits in well with the XDG standard, or whatever existing standard

or system your distribution chooses for filesystem layout in $HOME.

In order to make this work, you will want to customize your login shell startup

to include the directory in your PATH environment variable. It’s better to

put this into ~/.profile or whichever file your shell runs on login,

so that it’s only run once. That should be all that’s necessary, as PATH is

typically exported as an environment variable for all the shell’s child

processes. A line like this at the end of one of those scripts works well to

extend the system PATH for our login shell:

PATH=$HOME/.local/bin:$PATH

Note that we specifically put our new path at the front of the PATH

variable’s value, so that it’s the first directory searched for programs. This

allows you to implement or install your own versions of programs with the same

name as those in the system; this is useful, for example, if you like to

experiment with building software in $HOME.

If you’re using a systemd-based GNU/Linux, and particularly if you’re using a

display manager like GDM rather than a TTY login and startx for your X11

environment, you may find it more robust to instead set this variable with the

appropriate systemd configuration file. Another option you may prefer on

systems using PAM is to set it with pam_env(8).

After logging in, we first verify the directory is in place in the PATH

variable:

$ printf '%s\n' "$PATH"

/home/tom/.local/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/games

We can test this is working correctly by placing a test script into the

directory, including the #!/bin/sh shebang, and making it executable

by the current user with chmod(1):

$ cat >~/.local/bin/test-private-bindir

#!/bin/sh

printf 'Working!\n'

^D

$ chmod u+x ~./local/bin/test-private-bindir

$ test-private-bindir

Working!

Examples from the author

I publish the more generic scripts I keep in ~/.local/bin, which I

keep up-to-date on my personal systems in version control using Git, along with

my configuration files. Many of the scripts are very short, and are intended

mostly as building blocks for other scripts in the same directory. A few

examples:

gscr(1df): Run a set of commands on a Git repository to minimize its size.fgscr(1df): Find all Git repositories in a directory tree and rungscr(1df)over them.hurl(1df): Extract URLs from links in an HTML document.maybe(1df): Exit with success or failure with a given probability.rfcr(1df): Download and read a given Request for Comments document.tot(1df): Add up a list of numbers.

For such scripts, I try to write them as much as possible to use tools specified by POSIX, so that there’s a decent chance of them working on whatever Unix-like system I need them to.

On systems I use or manage, I might specify commands to do things relevant specifically to that system, such as:

- Filter out uninteresting lines in an Apache HTTPD logfile with awk.

- Check whether mail has been delivered to system users in

/var/mail. - Upgrade the Adobe Flash player in a private Firefox instance.

The tasks you need to solve both generally and specifically will almost certainly be different; this is where you can get creative with your automation and abstraction.

X windows scripts

An additional advantage worth mentioning of using scripts rather than shell

functions where possible is that they can be called from environments besides

shells, such as in X11 or by other scripts. You can combine this method with

X11-based utilities such as dmenu(1), libnotify’s notify-send(1),

or ImageMagick’s import(1) to implement custom interactive behaviour

for your X windows session, without having to write your own X11-interfacing

code.

Other languages

Of course, you’re not limited to just shell scripts with this system; it might suit you to write a script completely in a language like awk(1), or even sed(1). If portability isn’t a concern for the particular script, you should use your favourite scripting language. Notably, don’t fall into the trap of implementing a script in shell for no reason …

#!/bin/sh

awk 'NF>2 && /foobar/ {print $1}' "$@"

… when you can instead write the whole script in the main language used, and

save a fork(2) syscall and a layer of quoting:

#!/usr/bin/awk -f

NF>2 && /foobar/ {print $1}

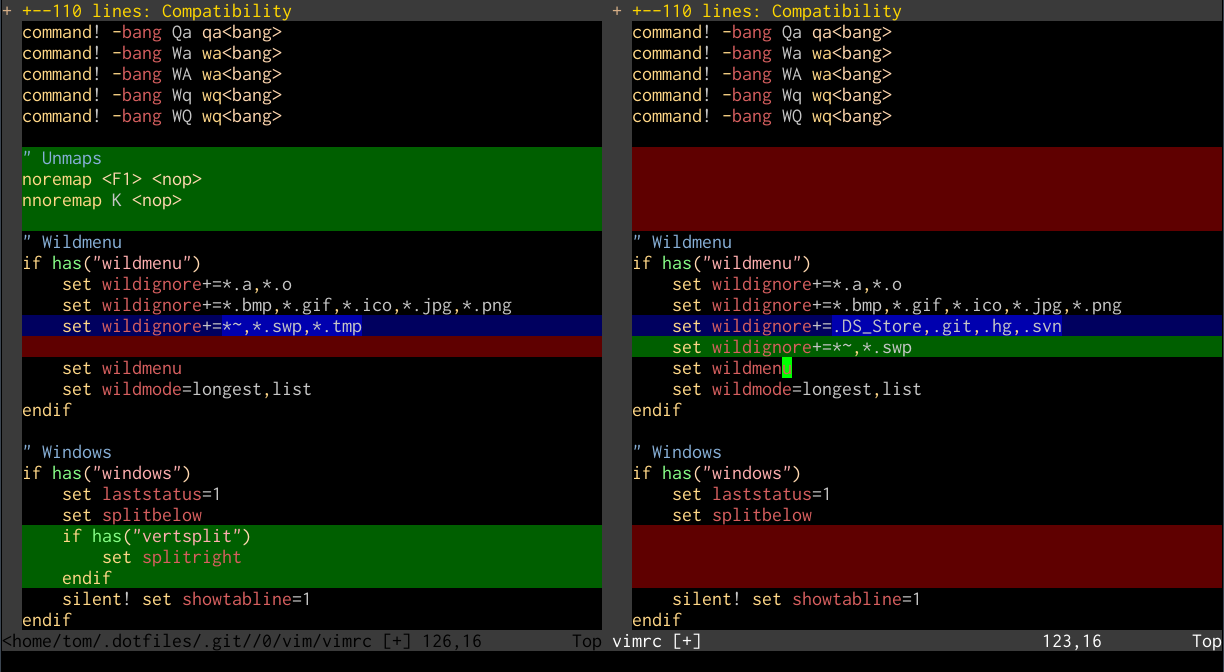

Versioning and sharing

Finally, if you end up writing more than a couple of useful shell functions and scripts, you should consider versioning them with Git or a similar version control system. This also eases implementing your shell setup and scripts on other systems, and sharing them with others via publishing on GitHub. You might even go so far as to write a Makefile to install them, or manual pages for quick reference as documentation … if you’re just a little bit crazy …