The text editor is the core tool for any programmer, which is why choice of editor evokes such tongue-in-cheek zealotry in debate among programmers. Unix is the operating system most strongly linked with two enduring favourites, Emacs and Vi, and their modern versions in GNU Emacs and Vim, two editors with very different editing philosophies but comparable power.

Being a Vim heretic myself, here I’ll discuss the indispensable features of Vim for programming, and in particular the use of shell tools called from within Vim to complement the editor’s built-in functionality. Some of the principles discussed here will be applicable to those using Emacs as well, but probably not for underpowered editors like Nano.

This will be a very general survey, as Vim’s toolset for programmers is

enormous, and it’ll still end up being quite long. I’ll focus on the

essentials and the things I feel are most helpful, and try to provide links to

articles with a more comprehensive treatment of the topic. Don’t forget that

Vim’s :help has surprised many people new to the editor with its high quality

and usefulness.

Filetype detection

Vim has built-in settings to adjust its behaviour, in particular its syntax

highlighting, based on the filetype being loaded, which it happily detects and

generally does a good job at doing so. In particular, this allows you to set an

indenting style conformant with the way a particular language is usually

written. This should be one of the first things in your .vimrc file.

if has("autocmd")

filetype indent plugin on

endif

Syntax highlighting

Even if you’re just working with a 16-color terminal, just include the

following in your .vimrc if you’re not already:

syntax on

The colorschemes with a default 16-color terminal are not pretty largely by necessity, but they do the job, and for most languages syntax definition files are available that work very well. There’s a tremendous array of colorschemes available, and it’s not hard to tweak them to suit or even to write your own. Using a 256-color terminal or gVim will give you more options. Good syntax highlighting files will show you definite syntax errors with a glaring red background.

Line numbering

To turn line numbers on if you use them a lot in your traditional IDE:

set number

You might like to try this as well, if you have at least Vim 7.3 and are keen to try numbering lines relative to the current line rather than absolutely:

set relativenumber

Tags files

Vim works very well with the output from the ctags utility. This allows

you to search quickly for all uses of a particular identifier throughout the

project, or to navigate straight to the declaration of a variable from one of

its uses, regardless of whether it’s in the same file. For large C projects in

multiple files this can save huge amounts of otherwise wasted time, and is

probably Vim’s best answer to similar features in mainstream IDEs.

You can run :!ctags -R on the root directory of projects in many popular

languages to generate a tags file filled with definitions and locations for

identifiers throughout your project. Once a tags file for your project is

available, you can search for uses of an appropriate tag throughout the project

like so:

:tag someClass

The commands :tn and :tp will allow you to iterate through successive uses

of the tag elsewhere in the project. The built-in tags functionality for this

already covers most of the bases you’ll probably need, but for features such as

a tag list window, you could try installing the very popular Taglist

plugin. Tim Pope’s Unimpaired plugin also contains a couple of useful

relevant mappings.

Calling external programs

Until 2017, there were three major methods of calling external programs during a Vim session:

:!<command>— Useful for issuing commands from within a Vim context particularly in cases where you intend to record output in a buffer.:shell— Drop to a shell as a subprocess of Vim. Good for interactive commands.- Ctrl-Z — Suspend Vim and issue commands from the shell that called it.

Since 2017, Vim 8.x now includes a :terminal command to bring up a terminal emulator buffer in a window. This seems to work better than previous plugin-based attempts at doing this, such as Conque. For the moment I still strongly recommend using one of the older methods, all of which also work in other vi-type editors.

Lint programs and syntax checkers

Checking syntax or compiling with an external program call (e.g. perl -c,

gcc) is one of the calls that’s good to make from within the editor using

:! commands. If you were editing a Perl file, you could run this like so:

:!perl -c %

/home/tom/project/test.pl syntax OK

Press Enter or type command to continue

The % symbol is shorthand for the file loaded in the current buffer. Running

this prints the output of the command, if any, below the command line. If you

wanted to call this check often, you could perhaps map it as a command, or even

a key combination in your .vimrc file. In this case, we define a command

:PerlLint which can be called from normal mode with \l:

command PerlLint !perl -c %

nnoremap <leader>l :PerlLint<CR>

For a lot of languages there’s an even better way to do this, though, which

allows us to capitalise on Vim’s built-in quickfix window. We can do this by

setting an appropriate makeprg for the filetype, in this case including a

module that provides us with output that Vim can use for its quicklist, and a

definition for its two formats:

:set makeprg=perl\ -c\ -MVi::QuickFix\ %

:set errorformat+=%m\ at\ %f\ line\ %l\.

:set errorformat+=%m\ at\ %f\ line\ %l

You may need to install this module first via CPAN, or the Debian package

libvi-quickfix-perl. This done, you can type :make after saving the file to

check its syntax, and if errors are found, you can open the quicklist window

with :copen to inspect the errors, and :cn and :cp to jump to them within

the buffer.

This also works for output from gcc, and pretty much any other compiler

syntax checker that you might want to use that includes filenames, line

numbers, and error strings in its error output. It’s even possible to do this

with web-focused languages like PHP, and for tools like JSLint for

JavaScript. There’s also an excellent plugin named Syntastic that

does something similar.

Reading output from other commands

You can use :r! to call commands and paste their output directly into the

buffer with which you’re working. For example, to pull a quick directory

listing for the current folder into the buffer, you could type:

:r!ls

This doesn’t just work for commands, of course; you can simply read in other

files this way with just :r, like public keys or your own custom boilerplate:

:r ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub

:r ~/dev/perl/boilerplate/copyright.pl

Filtering output through other commands

You can extend this to actually filter text in the buffer through external

commands, perhaps selected by a range or visual mode, and replace it with the

command’s output. While Vim’s visual block mode is great for working with

columnar data, it’s very often helpful to bust out tools like column, cut,

sort, or awk.

For example, you could sort the entire file in reverse by the second column by typing:

:%!sort -k2,2r

You could print only the third column of some selected text where the line

matches the pattern /vim/ with:

:'<,'>!awk '/vim/ {print $3}'

You could arrange keywords from lines 1 to 10 in nicely formatted columns like:

:1,10!column -t

Really any kind of text filter or command can be manipulated like this in Vim, a simple interoperability feature that expands what the editor can do by an order of magnitude. It effectively makes the Vim buffer into a text stream, which is a language that all of these classic tools speak.

There is a lot more detail on this in my “Shell from Vi” post.

Built-in alternatives

It’s worth noting that for really common operations like sorting and searching,

Vim has built-in methods in :sort and :grep, which can be helpful if you’re

stuck using Vim on Windows, but don’t have nearly the adaptability of shell

calls.

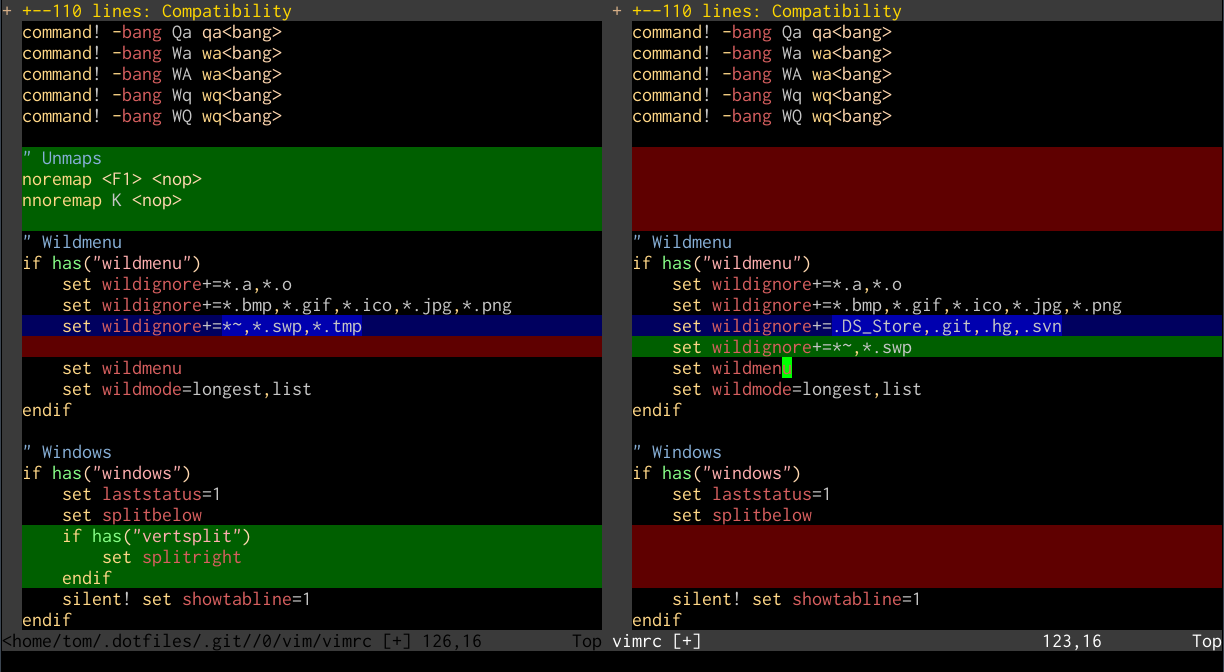

Diffing

Vim has a diffing mode, vimdiff, which allows you to not only view the

differences between different versions of a file, but also to resolve conflicts

via a three-way merge and to replace differences to and fro with commands like

:diffput and :diffget for ranges of text. You can call vimdiff from the

command line directly with at least two files to compare like so:

$ vimdiff file-v1.c file-v2.c

Version control

You can call version control methods directly from within Vim, which is

probably all you need most of the time. It’s useful to remember here that %

is always a shortcut for the buffer’s current file:

:!svn status

:!svn add %

:!git commit -a

Recently a clear winner for Git functionality with Vim has come up with Tim Pope’s Fugitive, which I highly recommend to anyone doing Git development with Vim. There’ll be a more comprehensive treatment of version control’s basis and history in Unix in Part 7 of this series.

The difference

Part of the reason Vim is thought of as a toy or relic by a lot of programmers used to GUI-based IDEs is its being seen as just a tool for editing files on servers, rather than a very capable editing component for the shell in its own right. Its own built-in features being so composable with external tools on Unix-friendly systems makes it into a text editing powerhouse that sometimes surprises even experienced users.